By , Senior Lecturer in Economics, Sheffield Hallam University and , Associate professor in Finance, ESC Pau

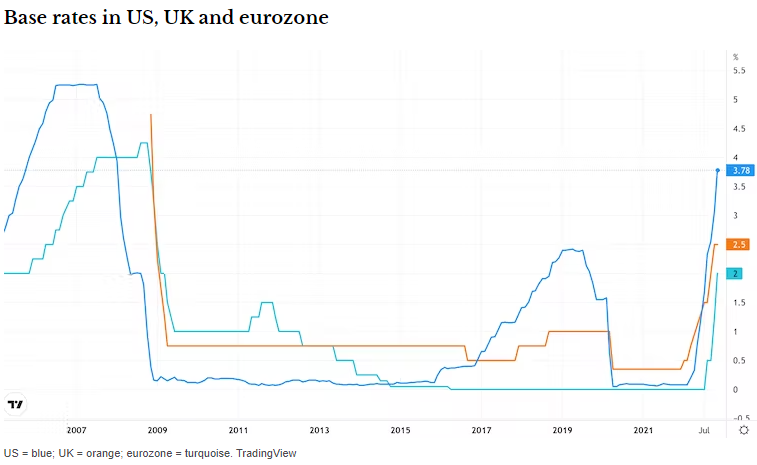

It’s decision time for central banks on interest rates again. After years of ultra-loose monetary policies, the Fed in particular has been aggressively raising interest rates during 2022 to counteract the inflation surge. All three central banks – the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) – increased their benchmark rates by 0.75 points at their meetings in late October/early November.

The Fed and BoE have also been reducing the amount of money in the economy through what is known as quantitative tightening. This involves removing the money they “created” via quantitative easing, and the ECB is likely to follow suit. Fed Chair Jay Powell signalled a probable slowdown a couple of weeks ago, causing markets to surge in response. On the other hand, there is still pressure to stay aggressive to keep on top of inflation: UK wage growth is a worry, for instance.

It boils down to a question of how many rate rises the world economy can take. Here’s what the potential damage looks like:

1. Consumption

Higher interest rates force people to pay more to service their debts, including mortgages, car loans, credit cards and more. With many debts, the damage is staggered because of short-term fixed rates below today’s market rates. But to take UK mortgages as an example, it is estimated that the average household will be forking out an extra £425 a month by the end of 2024. In London, the average increase will be closer to £700.

In a largely stagnant economy where wages are not keeping up with inflation, spending more on debts means cutting back on consumption – particularly on unessential spending such as holidays, luxury clothes or new cars. Companies will therefore produce less, sell less and earn less, causing two nasty chain reactions in the global economy: higher unemployment and slower growth. The silver lining is that it will probably reduce inflation faster.

2. Falling house prices

An oft-repeated mantra is that house prices cannot fall when there’s a limited supply of properties coming on the market. It’s not true, though. With mortgages getting more expensive, people can’t afford to pay as much for a house. Even if there are dozens of buyers competing for a property, each will bid lower than a year ago. The average buyer’s borrowing capacity is even more important than the number of buyers in the market. Higher interest rates could make rentals unprofitable for buy-to-let landlords, particularly since they typically pay higher interest rates than ordinary homeowners. A percentage of these landlords will sell, creating a temporary spike in the supply of properties on the market.

There’s also a self-fulfilling prophecy in that the more is written about falling prices, the more sellers will discount to sell quickly. Indeed, property prices have already started to fall. UK house prices fell by more than 2% in November, their third consecutive monthly fall and the sharpest since 2008. In the UK and also the US, analysts predict 5% to 10% falls within the next couple of years.

3. Developing country defaults

Most developing countries owe their debt in US dollars, not their local currency. Higher interest rates have strengthened the dollar – at least until it eased off recently – which has made their financial positions worse. This makes them seem like a riskier prospect to investors, making it more expensive for them to borrow on the international markets. It doesn’t help that many developing countries already have weakened public finances due to the pandemic. And the prospect of falling global consumption, an impending recession and reduced investment is not improving their credentials. Sri Lanka has already defaulted on its debts, and numerous other countries may soon follow. Their citizens can expect hyperinflation, deep recessions and excessive taxes in the battle to get finances under control. It can take years or even decades to recover, causing severe hardship.

4. Falling markets

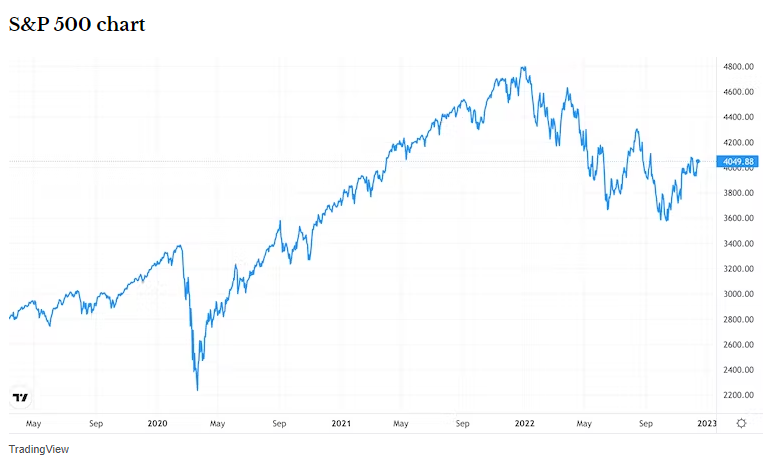

Just like property prices are affected by tighter monetary policies, the same is true of financial assets in general. Higher rates make it more lucrative to save money and invest in bonds, which makes it less tempting to invest in the stock market and other riskier assets. The prospect of reduced consumption and higher unemployment does not encourage investors to take risks either.

This is why financial markets have declined significantly during 2022 – and why they rallied on the news that rate hikes might decelerate. Banks have suffered over the past year because of a decline in stock market returns, while those in Europe have also been exposed to the Russia sanctions.

5. Political instability

Economic developments tend to be followed by political ones. From the French revolution to the Arab spring, high food prices have stirred revolutions. Brexit in the UK and the election of Donald Trump were also arguably reactions to economic insecurity. So the higher that interest rates rise, the greater the risk of political instability. Don’t be surprised if citizens ramp up their opposition to global elites and weak groups such as minorities and migrants. Also expect more populism and governments resorting to distractions such as nationalist wars.

The role of governments

Central banks will only actually reduce interest rates once inflation comes back to low levels. In the meantime, the global economy needs steady and wise governments to minimise the damage. Loan repayment holidays for struggling households and otherwise healthy businesses can certainly help. Food banks and free school meals are also essential, while governments need to have the courage to make billionaires, multinationals and even landlords pay their fair share of tax. Without policies like these, the next couple of years will be harder than is necessary.