The World Cup is said to boost consumer spending, particularly of food and drink, but how much do UK retailers really benefit from the tournament? Hann-Ju Ho, Senior Economist at Lloyds Bank Commercial Banking, looks at the evidence.

The World Cup is often said to boost consumer spending, particularly on food and drink and products like TVs, football kits and merchandise – but does the data bear that out? One recent estimate from the Centre for Retail Research ventured that the World Cup would add an extra £1.3bn to the economy, and £2.7bn if England reach the final.

Even if the latter figure only represents just over 0.1 per cent of annual GDP, it would nevertheless represent a significant boost to the retail sector. By comparing official UK retail sales figures for the May to July period in World Cup and non-World Cup years, it’s possible to examine whether UK retailers can really expect to benefit from the World Cup in Russia, and how much value it will deliver.

Soccer sales

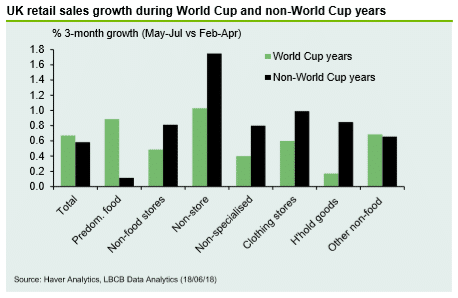

Analysing data gathered since 1988, Lloyds Bank decided to put the ‘World Cup effect’ to the test. We calculated the three-monthly growth rates of retail sales volumes over the May-July period for each World Cup year, then compared the average growth rates with non-World Cup years.

Figure 1 Retail sales growth in World Cup and non-World Cup years

The graph above reveals that in World Cup years, growth in total retail sales averaged 0.7% over the May-July period, which is marginally higher than 0.6% in non-World Cup years. So, at a first glance there doesn’t seem to be a significant material difference. But by breaking down the figures, we can see the situation is more nuanced.

In World Cup years, sales growth in ‘predominantly food stores’, such as supermarkets, averaged 0.9%, in significant contrast to non-competition years when it averaged only 0.1%.

And we even saw the ‘World Cup effect’ in action during the 1994 World Cup in the USA, when England failed to qualify for the competition.

Food store sales in May-July of that year still rose by 1.2%, though the most successful tournament for boosting growth was Germany 2006, when they rose by 1.3% as England progressed to the quarter finals.

But what about non-food sales – which would include products like TVs, football kits and merchandise – and ‘non-store’ sales?

Fans and non-foods

The figures suggest that stronger supermarket sales during World Cup years are partly offset by lower sales in non-food and non-store sales.

Non-food sales in May-July during years without the World Cup averaged 0.8%, compared with 0.5% in World Cup years – that’s reflected in softer sales growth in non-specialised (department) stores, clothing and footwear and household goods.

Non-store sales – which reflect retailers without a high street presence – also performed more strongly in non-World Cup years, averaging 1.7% compared with 1% in World Cup years, although that might also reflect the strong growth in internet sales.

Data limitations

Does this suggest that the World Cup only results in stronger sales of food and drink, rather than non-food products?

It’s worth remembering that supermarkets have strengthened their sales of non-food items, including TVs and clothing, in recent years.

Such sales are captured in the statistics as ‘predominantly food stores’ by virtue of the classification of the retailer.

Another point worth considering is that UK retail sales figures capture spending on ‘goods’, but not ‘services’, so the World Cup effect may be even bigger.

Retail sales for example, don’t include pubs and restaurants, or plane tickets to Russia.

Others might fancy having a flutter on England to win the competition, but that wouldn’t show up in the retail sales figures either.

We’ll certainly be hoping the 2018 team goes all the way, and that any feel-good factor is felt on the UK high street too.

Be the first to comment on "Is the ‘World Cup effect’ real?"